The COVID-19 pandemic revealed and amplified health inequities across the globe. The disease affected marginalized communities more severely, while global vaccine inequity likely prolonged the pandemic. This has led to calls to make global health research more inclusive, which would involve valuing and fostering the contributions of marginalized groups and lower- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and being mindful of their unique needs. Such an effort would not only help address prevailing disparities but also improve public health in general through sharing and incorporation of diverse perspectives.

Bangladesh, with a population of 169 million people living at a density of more than 1200 individuals per km2, was particularly vulnerable to a highly transmissible respiratory pathogen like SARS-CoV-2. According to the WHO, Bangladesh had 5.69% and 11.5% increases in excess deaths — compared to a period before the pandemic — in 2020 and 2021, respectively. This compared relatively favorably to global increases of 7.97% and 18.3% over the same period, with Bangladesh faring better than about half the world. Stringent lockdowns, efficient vaccination, and urban centralization slowing spread to rural areas early on likely contributed to Bangladesh’s modest success.

Existing public health and disease surveillance infrastructure was not only key to shaping pandemic control strategies but also helped make important research contributions about COVID-19, providing a model of how locally informed public health research can have far-reaching global impact. In the aftermath of the WHO declaring the end to COVID-19 as a global health emergency, it is instructive to look at some of Bangladesh’s contributions, as examples of the possibilities of inclusive global health research.

Backdrop

Over the past three decades, Bangladesh has made enormous strides in economic development and public health. Following independence in 1971, a history of natural disasters and famines, and the aftereffects of war led the country to be the subject of extensive international development work and public health research. Local infrastructure and expertise in these areas developed concurrently.

Non-governmental organizations like Institute for Poverty Action and Save the Children continue to perform important humanitarian work in their domains. The International Centre for Diarrheal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b), was set up to locally respond to the cholera crisis in the 1960s, and has since become a leader in global health research, tackling everything from infectious disease to the health impact of climate change.

Epidemiology and surveillance

Nationally reported statistics on SARS-CoV-2 are limited by the prevalence of testing. A more accurate way to measure COVID-19 burden is to estimate excess mortality during the pandemic compared to a pre-pandemic period. In 2021, icddr,b reported a 28% increase in excess mortality among the elderly as early as between January and April of 2020 in Matlab — a rural area in Bangladesh with a Health and Demographic Surveillance System. This highlighted the limitations of testing-based statistics long before the WHO published estimates of excess mortality during the pandemic, and influenced Bangladesh’s prioritization of the elderly in their vaccine rollout.

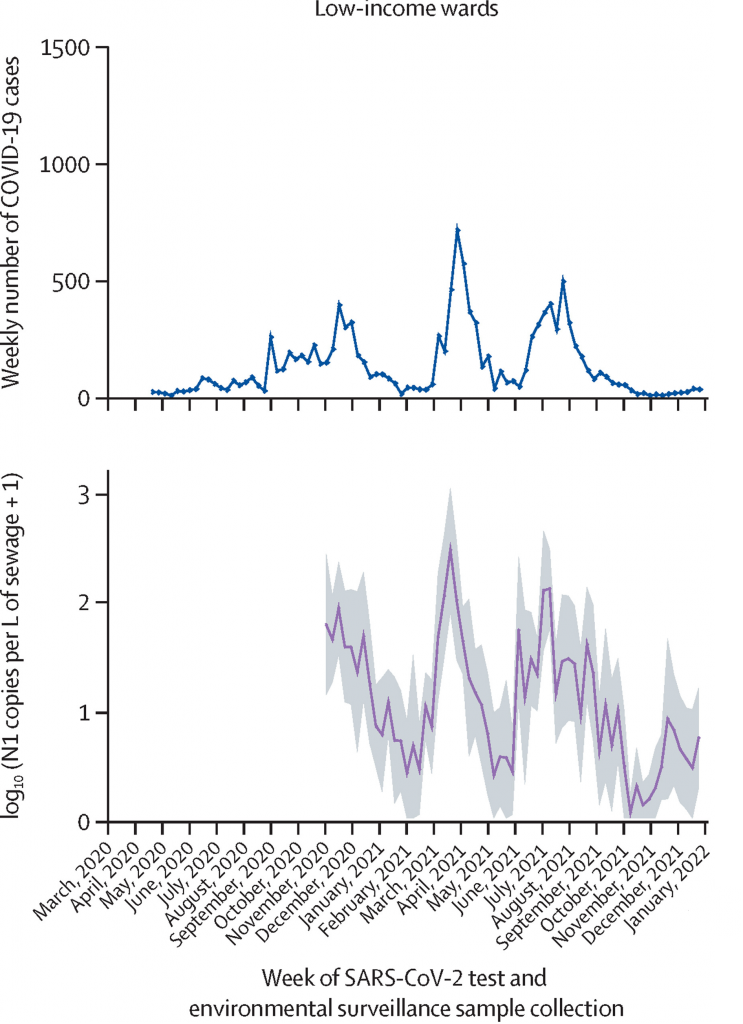

Environmental surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 was recognized early on as a way to track disease burden at the population level while avoiding bias in availability or use of testing. From the beginning of the pandemic, local researchers reported the SARS-CoV-2 burden across the sewage network in Dhaka every week to the national COVID-19 task force, providing important information on community transmission to drive public health policy. A recent analysis of this data alongside clinical data from across the city revealed that environmental surveillance was able to detect rise in cases in the surveilled area about 1-2 weeks advance.

Some of the results from Rogawski McQuade et al. 2023, showing that wastewater surveillance effectively tracked COVID-19 cases

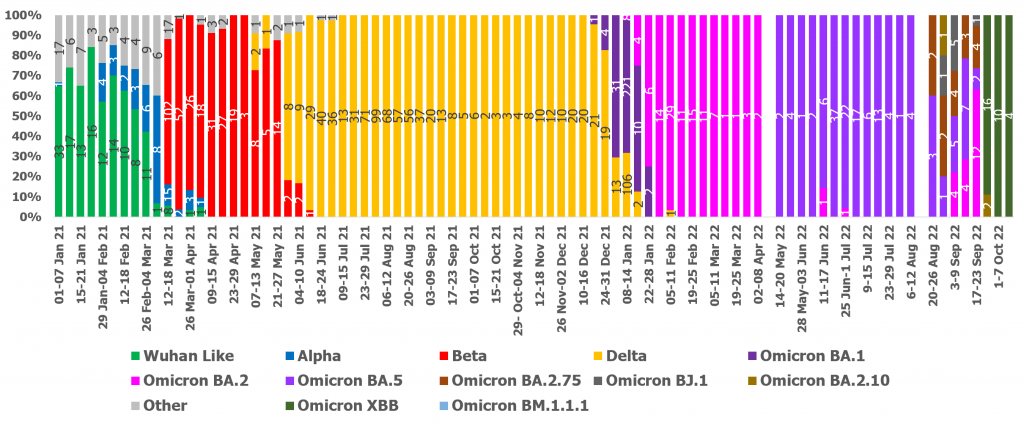

Finally, individual organizations and a partnership between several national health and research agencies — collective called the National Genomic Surveillance — tracked the emergence and spread of SARS-CoV-2 variants in Bangladesh using genome sequencing of clinical isolates of the virus, and deposited thousands of SARS-CoV-2 genomes in global sequence repositories to help international researchers study the evolution of the virus through the pandemic.

Genomic surveillance allowed tracking of circulating and emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants during the pandemic. Here, we see the weekly distribution of circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants in Dhaka city from 1 Jan 2021 to 14 Oct 2022. The bar graph (Y-axis) indicates the % of variants identified, and numbers are printed inside.

Community masking

Masks have been a surprisingly polarizing subject in many parts of the world, which was not helped by contradictory guidelines from different health governing bodies during early stages of the pandemic. A large, randomized cluster trial conducted in Bangladesh as a collaboration between local and international institutions has provided strong evidence for the effectiveness of community masking.

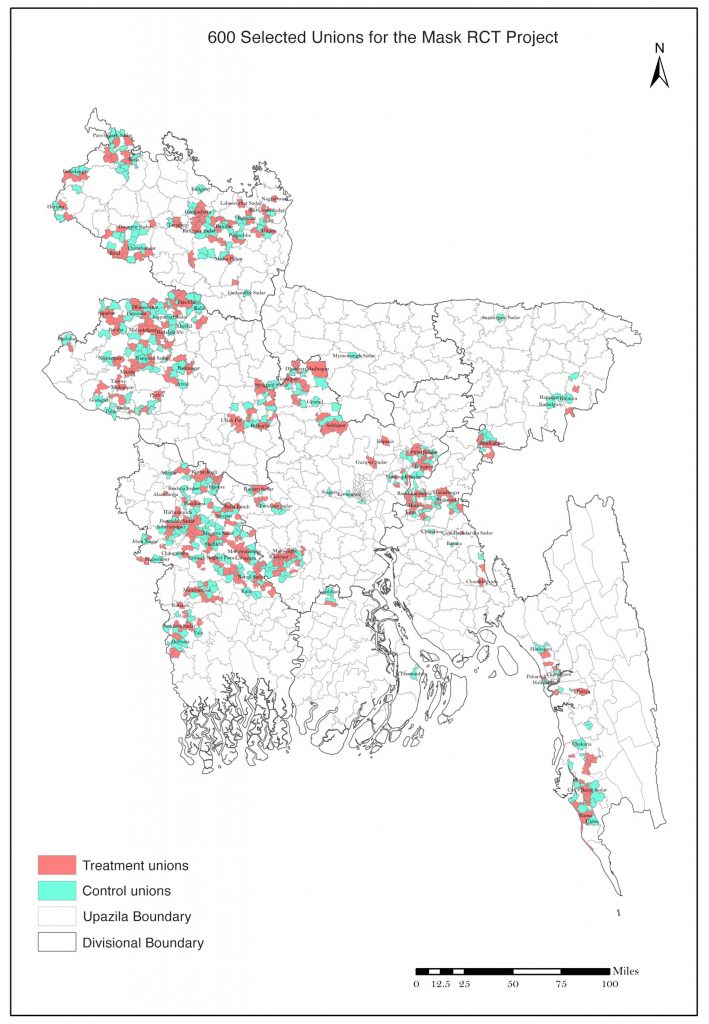

With the help of a grassroots network of volunteers, the authors studied the effects of mask promotion and use — or their absence — in 600 villages spanning Bangladesh. Mask promotion increased mask use by about 29%, and even non-universal community masking led to an about 10% reduction in symptomatic COVID-19. The study also showed that contrary to common belief, masking did not increase the frequency of high-risk behavior. These findings are likely to play a key role in shaping future strategies for the control of epidemics of respiratory pathogens.

Map showing the geographical extent of the community mask use study conducted in Bangladesh. From Abaluck et al. 2022

Long COVID

Long COVID refers to a set of neurological, cardiovascular, and other physiological sequelae that arise following COVID-19 infection. The condition is of great concern in a world where most people have been infected by the virus at least once, but it has frequently been dismissed. Part of the dismissal has to do with the lack of immediately observable evidence.

icddr,b published one of the first longitudinal studies in LMICs looking at the progression of long COVID, in which patients were followed for six months after recovery to record post-COVID symptoms. The study revealed that long-term complications were particularly common in individuals who had been hospitalized for COVID-19 and the elderly. Complications included increased risk of incident diabetes — consistent with other recent work on long COVID — and increased risk of uncontrolled blood sugar in patients with pre-existing diabetes.

Looking ahead

As the pandemic has progressed, it has been necessary to generate data on its impact and evidence for the success of various mitigation strategies at unprecedented speeds to help shape an effective response. Local and international organizations in Bangladesh have stepped up to perform SARS-CoV-2 surveillance, evaluate interventions, and study the novel pathogen and disease, contributing important knowledge as well as providing a model for decentering global health research and narratives.

Global funding bodies must prioritize developing research and public health infrastructure in LMICs, empowering researchers in marginalized groups, and promoting equitable collaborations to share resources and expertise. Doing so will lead to more discoveries of both local and global relevance and increase the impact of global health research.

Developing research and public health capacity in the global South is also important in the specific context of future pandemics. Most of the infectious diseases currently prioritized by the WHO as posing a high risk of causing a pandemic occur in the tropics, often in countries that would benefit from expertise in surveillance and control of the pathogens; Bangladesh again shows a way forward with its active surveillance of pathogens like cholera, influenza, and the highly lethal Nipah virus. Moreover, as the COVID-19 pandemic has shown, emerging diseases can spread faster than ever before in an increasingly mobile world. Combating pandemics will always require concerted global efforts built on local expertise.