Immunisation is one of the most successful and cost-effective means of saving lives. It is a simple and effective measure to protect children (and adults) from serious diseases, giving them the best start to a healthy future. Additionally, not only does immunisation protect the individual, but also greatly benefits the wider community by minimising the spread of diseases.

Immunisation will protect against a variety of dangerous childhood diseases, including pertussis (whooping cough), measles, rubella (German measles), meningococcal C, pneumococcal disease, chickenpox (varicella), tetanus, mumps, polio, diphtheria, rotavirus and hepatitis. Each of these diseases cause serious health problems and can sometimes prove fatal.

Immunisation works by teaching the immune system to imitate a natural infection. Each vaccine contains a small dosage of the virus and once the vaccine has been administered, the body develops antibodies which help to fight the virus. What remains is a concentration of cells which the immune system can recognise and neutralise should the person come into contact with the virus, thus preventing the disease from developing or greatly reducing its severity.

The Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) was introduced in Bangladesh in 1979 as a pilot project, but coverage was a lowly 2 per cent until 1985 when the government began to expand the programme in phases. It is considered as one of the most successful public health interventions. As of 2014, 84 per cent of children aged 12-23 months had received all recommended vaccinations, and more than one million lives have been saved through this initiative.

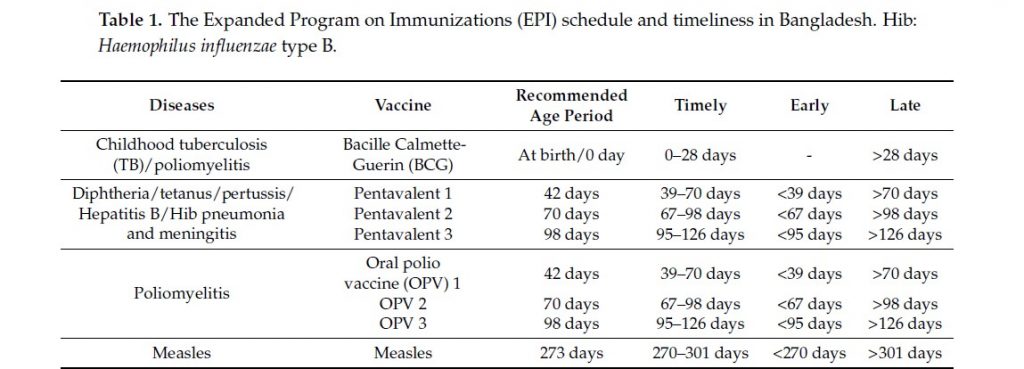

The immunisation guideline for Bangladesh states that a child is considered fully vaccinated when they have received one dose of the vaccine against tuberculosis – Bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG), three doses of a pentavalent vaccine, three doses of the polio vaccine, and one dose of the measles and rubella vaccine. If a child has not received any of the recommended doses, especially during the specified vaccine schedule (Table 1), they are considered as partially vaccinated.

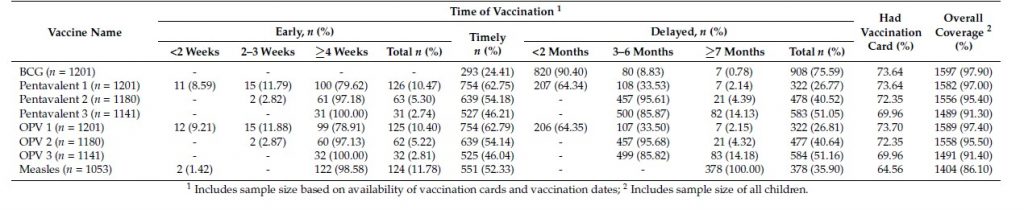

Despite the immense success of EPI, many children do not complete their vaccination by the recommended age periods. Parents often neglect to immunise their child with the subsequent second and third dosages. icddr,b researchers conducted an in-depth examination of the determinants for incomplete immunisation in Bangladesh. They analysed 1,631 children aged 12-23 months from the latest Bangladesh Demographic Health Survey 2014 dataset, categorised by whether they had received the vaccines according to the schedule. The number of fully immunised children was 84 per cent, a positive marker of the successful EPI programme. However, partially immunised and non-immunised children were at 14 per cent and 2 per cent respectively.

While there is a greater proportion of immunised children, they are not receiving timely vaccinations. A reported 76 per cent children had delays in receiving BCG, 51 per cent for pentavalent 3, and 36 per cent for measles (Table 2). A variety of factors contribute to this issue. Some factors, such as birth order and the number of children in a household, did influence the failure of timely administration of multi-dose vaccines (e.g. pentavalent) but this was not observed in the case of single-dose vaccines like BCG. Children born to large households, belong to the lower socio-economic quintiles, and have poor access to drinking water and hygienic facilities are more predisposed to missing vaccines

(Sources: Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2018, 3, 72)

Maternal education and awareness were also significant contributing components of success. Children of mothers with higher level of education are aware of community clinics (where vaccines are given) and are more likely to receive multi-dose vaccines according to the schedule.

Interestingly, the research showed a greater prevalence of failure to receive the BCG and measles for children of unemployed mothers although this was not observed with pentavalent vaccines. This is contradictory to previous studies and the authors surmised that this could be due to unemployed mothers engaging full time in non-formal sectors (e.g. domestic work). Additionally, they are not financially empowered and that may isolate them from the available service related information, which might be another reason for not coming to the vaccination site on time.

“Delayed or incomplete immunisation could be associated with serious health consequences, which often increases the household’s healthcare expenditure. Many low-income households could face catastrophic economic burden if this were to continue. Thus, if we want to receive the broader economic benefits of the immunisation programme, we should focus on these important issues” says Abdur Razzaque Sarker, health economist researcher and assistant scientist of icddr,b who led this study.

To ensure that children are receiving all their vaccines according to the schedule, more targeted public awareness programmes need to be developed and utilised, with a special focus on the importance of timely immunisation and information on the availability of such services in each locale. Moreover, resources need to be allocated to educating mothers on the vaccine schedule; this is imperative as the majority of pregnant women in Bangladesh will give birth at home without the presence of skilled birth attendants, thus raising the probability of an unvaccinated child.