“Gender-based violence is perhaps the most widespread and socially tolerated of human rights violations”

– UNFPA State of World Population 2015

The International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women, observed annually on 25 November, marks the beginning of the 16 Days of Activism against Gender Based Violence (concluding on 10 December – Human Rights Day).

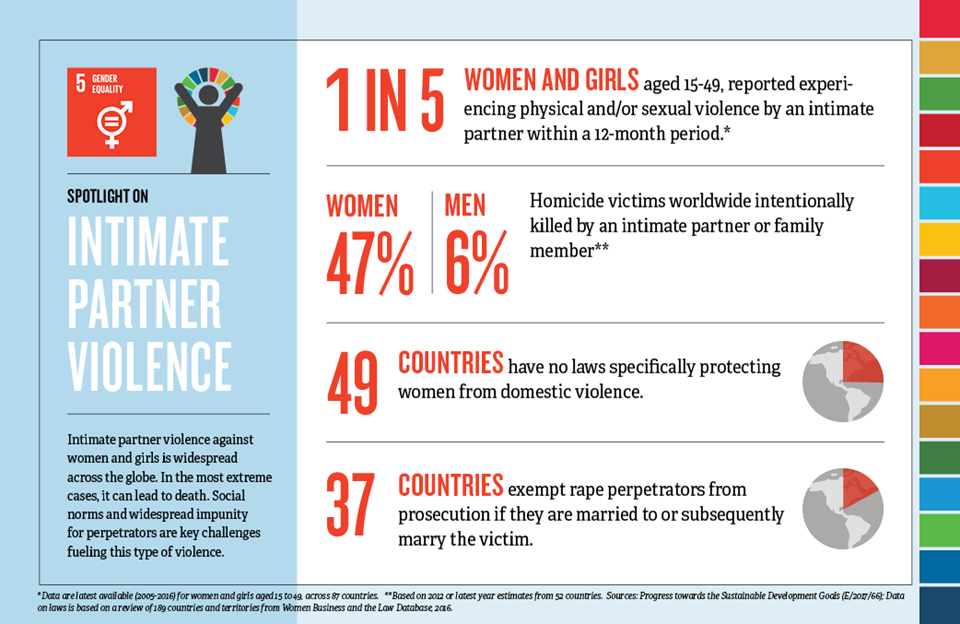

The United Nations (UN) defines violence against women as “any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or mental harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life”. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 1 in 3 women worldwide have experienced or will experience some form of physical and/or sexual violence in their lifetime.

Reducing violence against women, particularly intimate partner violence (IPV), is one of the core aims of Goal 5 of the Sustainable Development Goals, which aims to “achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls”.

IPV is a form of domestic violence committed by one partner against the other in an intimate relationship, such as a spouse. It is often used as a method of coercive control. Many female victims of IPV do not seek help due to socio-cultural stigma surrounding the issue, as well as a fear of the abuser.

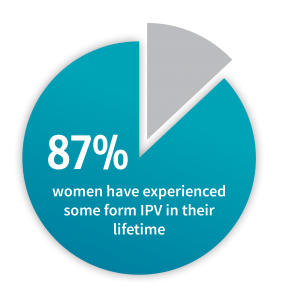

In Bangladesh, as many as 87 per cent of women have experienced some form of physical and/or sexual violence from an intimate partner in their lifetime. Gender inequality is one of the main predictors of IPV occurrence, and Bangladesh is ranked 119 (out of 188 countries surveyed) on the United Nations Development Programme’s Gender Inequality Index.

There has been extensive research on the effects of such violence on female victims, without exploring and understanding the behaviours, practices, and ideals which effectuate IPV behaviours in men. Understanding the psychosocial factors that perpetuate IPV in Bangladesh could help design interventions to prevent men from committing these behaviors in the first place.

In order to address this gap in knowledge, two recent publications from icddr,b investigated how factors like societal norms, exposure to childhood abuse and life satisfaction contribute to men’s perpetration of intimate partner violence (men are almost exclusively the offenders of IPV, especially in the context of Bangladesh).

In the first study, the authors interviewed 1,572 currently or previously married men from both urban and rural settings, and analysed the association between committing different abusive behaviours and self-reported life satisfaction. The study analyses the differences between two categories of partner abuse – controlling behaviours and physical/psychological IPV – in terms of their psychosocial impact on the men committing them.

Controlling behaviours, such as deciding how female partners should dress and who they should spend time with, were associated with higher self-reported life satisfaction among men. The authors conclude that these controlling behaviours are not only normalised, but also internalised by men in Bangladesh as part of marriage. This allows men to experience positive psychosocial outcomes from successfully using controlling behaviour in intimate relationships.

By contrast, committing physical and psychological IPV – such as beating or publicly humiliating female partners – was associated with lower self-reported life satisfaction in men. A probable interpretation may be that these types of violence, although normative in this society, have not yet been internalised by men. Even in a patriarchal setting like Bangladesh, IPV does not appear to lead to positive psychosocial outcomes in men committing it.

The authors conclude that interventions to promote alternative views of non-violent masculinity could allow men to meet their psychological needs within a marriage without relying on violent or controlling behaviour.

The second study explores connections between childhood exposure to violence, community gender norms and male propensity to commit IPV.

The authors interviewed 570 young married men (aged between 18-34 years) from 50 urban and 62 rural settlements, and found that almost half of the men admitted to committing physical IPV. 64 per cent of the men interviewed had been exposed to violence as children, and those with greater exposure to violence as children were more likely to commit IPV as adults. This finding corroborates previous studies in resource-poor countries that linked childhood exposure to violence with a higher risk of committing IPV in adulthood.

The study also examined how variation in community gender norms can affect the propensity to commit IPV. Community gender norms were assessed by measuring responses of 938 senior male community members (aged 35-49) to statements about the role of women and the acceptability of violence against women.

There was significant variation in attitudes about gender equality among the communities assessed. Men from more gender-equitable communities were less likely to commit IPV; however, the risk of perpetrating IPV was not lower among men exposed to childhood abuse in more gender-equitable communities. Thus, interventions both on gender norm change and prevention of violence against children are essential in addressing IPV perpetration by men.

These two studies show that while violence against women is prevalent in nearly all societies, interventions simply aimed at assisting women are not sufficient to properly address this issue. Research from advocacy efforts has indicated that prevention strategies need to employ a holistic approach to actualise long-lasting effect.

Understanding how normative masculine behaviour patterns are formulated, especially in children exposed to violence, can help formulate preventive interventions targeting men in their early years. These interventions could reduce the incidence of IPV, and contribute to a decline in violence against women and those unable to defend themselves.